Discrete CKKS Functional Bootstrapping

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) allows arbitrary computations on encrypted data. The Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song (CKKS) scheme is particularly efficient for approximate arithmetic over real and complex numbers, making it a cornerstone for privacy-preserving machine learning. However, CKKS traditionally struggles with discontinuous functions, such as those represented by lookup tables (LUTs), which are essential for many algorithms. Functional Bootstrapping and Discrete CKKS extend the standard noise-refreshing bootstrapping procedure to evaluate an arbitrary function “for free” during the refresh cycle. This post provides a technical overview of how functional bootstrapping was first adapted for CKKS and how subsequent research enabled the efficient evaluation of very large LUTs.

Classical CKKS bootstrapping

In CKKS, each homomorphic multiplication consumes a multiplicative level. Once a ciphertext becomes “exhausted” - that is that it consumed all of its original multiplicative levels - no further multiplications can be performed. Classical CKKS bootstrapping is a procedure to restore multiplicative depth.

The high-level procedure consists of four main steps:

- $\textsf{ModRaise}$: The modulus of the exhausted ciphertext is raised to a much larger value. This operation regains modulus space for further computations but adds integer overflows to the plaintext message. The encrypted message becomes $t(X) = m(X) + q_0 \cdot I(X)$, where $q_0$ is the original small modulus and $I(X)$ is a polynomial representing the overflow.

- $\textsf{CoeffsToSlots}$: The polynomial coefficients of $t(X)$ are homomorphically encoded into the plaintext “slots” of a new ciphertext. This allows element-wise operations on the coefficients.

- $\textsf{EvalMod}$: A polynomial approximation of a trigonometric function, typically a sine wave, is evaluated on the slots. This approximates the modular reduction $t_i \pmod{q_0}$, effectively removing the overflow term $q_0 \cdot I(X)$ while preserving the original message $m(X)$.

- $\textsf{SlotsToCoeffs}$: The cleaned message in the slots is homomorphically decoded back into a polynomial coefficient representation, yielding a “fresh” ciphertext with reduced noise.

Hermite interpolation

The key to turning classical bootstrapping into functional bootstrapping is to replace the $\textsf{EvalMod}$ step with a procedure that not only removes overflows but also applies a desired function $f$ to the message. The challenge is to do this without adding excessive noise, especially given the approximate nature of CKKS.

The solution lies in (trigonometric) Hermite interpolation. Unlike standard interpolation which only matches function values at given points, Hermite interpolation also matches the values of one or more derivatives. For functional bootstrapping, we construct a trigonometric polynomial $R(x)$ that satisfies two conditions for all integers $k$ in the domain $\mathbb{Z}_p$:

- $R(k/p) = f(k)$

- $R'(k/p) = 0$

The second condition -setting the first derivative to zero- is crucial for noise management. For a message $m_i = k/p$ with a small input error $\varepsilon_{in}$, the Taylor expansion of the evaluation is $R(m_i + \varepsilon_{in}) \approx R(m_i) + R'(m_i)\varepsilon_{in} + \frac{R''(m_i)}{2}\varepsilon_{in}^2$.

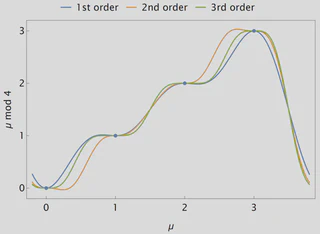

By forcing $R'(m_i) = 0$, the output error becomes proportional to $\varepsilon_{in}^2$, achieving quadratic noise reduction. Higher-order interpolations can set more derivatives to zero for even greater noise cleaning at the cost of higher computational complexity. Below is a plot of the identity function on $\mathbb Z_4$ for the first, second and third order Hermite interpolation.

Pluging it in CKKS bootstrapping

The method developed by Alexandru, Kim, and Polyakov, which we’ll call AKP-FBT, integrates trigonometric Hermite interpolation directly into the CKKS bootstrapping pipeline. The process is as follows:

- An input RLWE ciphertext, encrypting values in $\mathbb Z_p$, is converted to an exhausted CKKS ciphertext.

- The standard $\textsf{ModRaise}$ and $\textsf{CoeffsToSlots}$ procedures are applied.

- The $\textsf{EvalMod}$ step is replaced by an $\textsf{EvalLUT}$ step. This step evaluates a Chebyshev interpolation of $E(x) = e^{2\pi i x}$ instead of $\sin$, and the trigonometric Hermite polynomial $R(x)$ corresponding to the target function $f$. The polynomial is expressed as a power series of degree $p-1$ in $E(x) = e^{2\pi i x}$.

- The result is converted back to an RLWE ciphertext via $\textsf{SlotsToCoeffs}$ and a final modulus switch.

This elegant approach provides a general functional bootstrapping capability for CKKS. However, its main bottleneck is the degree of the polynomial interpolation, which is $p-1$ for a LUT of size $p$. This makes the direct evaluation of LUTs larger than approximately 14 bits impractical due to prohibitive computational costs and parameter requirements.

Faster and larger LUTs

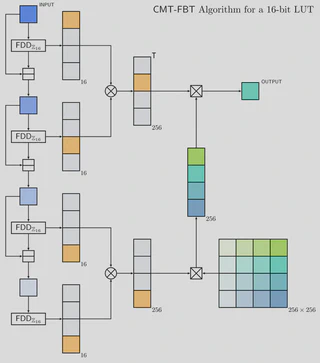

To overcome the limitations of AKP-FBT for larger LUTs, we developed novel algorithms inspired by multiplexer-based methods used in other FHE schemes. The most performant of these is the Collapsed Multiplexer Tree Functional Bootstrapping (CMT-FBT) method.

Instead of evaluating one high-degree polynomial, CMT-FBT decomposes the problem.

The high-level workflow is:

- Functional Digit Decomposition (FDD): The input ciphertext, encrypting a value in $\mathbb{Z}_P$, is homomorphically decomposed into several ciphertexts, each encrypting a digit of the original value in a smaller base $p$ (e.g., $P=2^{16}$, $p=2^4$). This step leverages Multi-Value Bootstrapping (MVB), an extension of AKP-FBT that evaluates multiple LUTs in a single bootstrapping operation with little overhead. FDD uses MVB to simultaneously extract the digits and evaluate the necessary Kronecker delta functions ($\delta_{x_j, k}$) on them.

- Collapsed Multiplexer Tree (CMT): The encrypted Kronecker delta functions are used as selectors in a shallow, $p$-ary multiplexer tree that selects the correct value from the LUT. The tree evaluation is implemented with Kronecker products and carefully optimized for the CKKS scheme to minimize multiplicative depth and the cost of scalar multiplications.

This decomposition dramatically improves performance and scalability. The multiplicative depth of the tree is only $O(\log\log_p P)$, and the overall complexity scales much more favorably with the LUT size $P$. For a 16-bit LUT, CMT-FBT achieves a 47.5x speed-up in amortized time over AKP-FBT in a single-threaded setting, and exposes good parallelization. This breakthrough makes the homomorphic evaluation of arbitrary functions on inputs up to 20 bits practical on commodity hardware.

Below is the workflow of the evaluation of a 16-bit LUT using 4-bit digits.

For more detail, we refer an interested reader to the both papers: AKP-FBT & CMT-FBT